Ancient Roman

(H 21 1/4 × W 18 7/8 × D 17 3/4 inch)

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

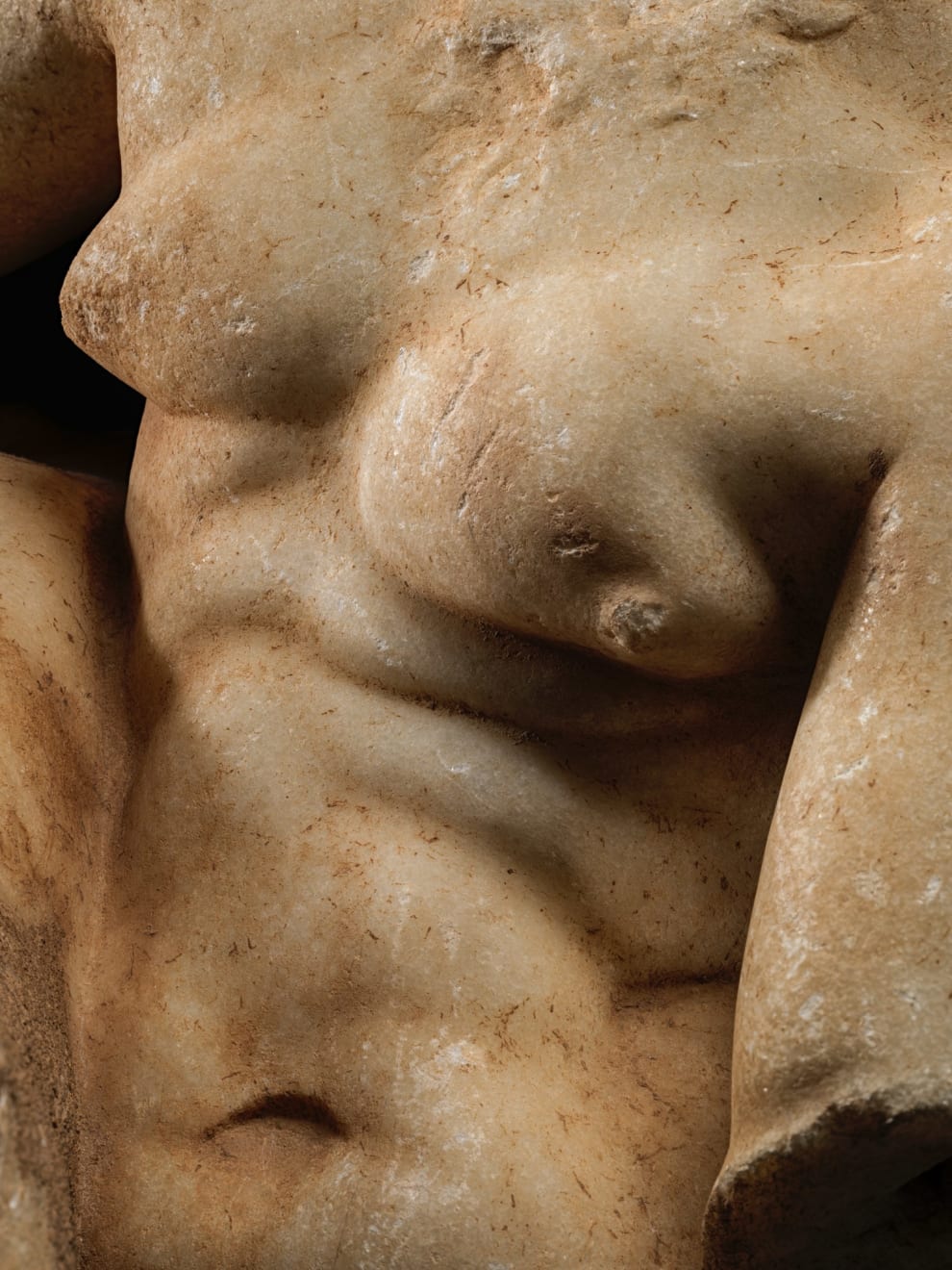

The torso before us represents one of the most prevalent and favoured sculptural motifs among the wealthy families of the Roman ruling class. The depiction of Silenus with a wineskin—commonly referred to as culleus in Latin— directly references sculptures associated with the Dionysian sphere, a well- recognised and esteemed theme in the imperial world. Although carved from Greek white marble, it cannot be ruled out that the statue may have been crafted in a workshop in Rome itself.

According to mythological tradition, Silenus was the principal mentor and guardian of the young Dionysus, entrusted to him by the god Hermes1. From this point forward, Silenus remained inextricably linked to the god of wine and the mysteries associated with him (fig. 2). One of the most renowned myths surrounding Silenus involves King Midas. During Dionysus' return from India, the perpetually inebriated Silenus strayed from the jubilant procession and became lost in the rose gardens of the Phrygian king.

King Midas, after taking him in, cared for the elderly, rotund mentor for several days until Silenus was reunited with the procession from which he had inadvertently strayed2. The figure of Silenus is symbolically associated with the wisdom that emerges through intoxication, further accentuated in his animalistic traits when transformed into Papposilenus—a variant marked by obesity and pronounced hirsuteness (fig. 3).

The piece before us was most likely employed as a decorative element in a private estate during the imperial period, while in the Renaissance it was repurposed to adorn a garden, evidently with aquatic features. The back of the Silenus—where a small goat’s tail is also visible—exhibits numerous calcareous encrustations, suggesting its placement near a fountain or, more plausibly, within a nymphaeum, where the statue may have been displayed in a niche.

Numerous examples of such re-use can be cited, including Villa Doria Pamphilj, Villa Albani, Villa Torlonia, Villa Borghese, Palazzo Caffarelli, Newby Hall, and the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, to name a few. The presence of multiple holes in the sculpture indicates subsequent modifications, likely for the insertion of iron rods to secure additional elements. These could represent either ancient or more modern restorations, reflecting a practice not uncommon in both late antiquity and the Renaissance.

The model that has come down to us closely resembles the renowned “Cesi” type, part of the Torlonia collection, which originally belonged to the Giustiniani family (figs. 4-5). It is therefore plausible to suggest that this sculptural type draws stylistically from models by Lysippus and workshops of the Hellenistic period. A comparable example is the Silenus from Villa Albani (fig. 6), which, unlike the “Cesi” type, does not rest on a modern base featuring a panther.

Provenance

Private Collection, (Switzerland, acquired prior to 1966)Public Auction, (London, June 2016)